From Sierra Leone Studies, No.

2, June, 1954

The Origins of Tribal Administration

in Freetown,(part 2)

By Michael Banton

they were turned out into the streets

of the town. The Vagrancy

Ordinance met this sort of complaint by giving Tribal Rulers power to

inquire into what members of their tribes were doing in Freetown. If

they

were without employment for three weeks or more the Tribal Ruler could

bring them before the Police Magistrate, have them declared “ idle and

disorderly persons” and send them back to their Chiefdoms. The Manual

Labour Ordinance changed the position of the Tribal Ruler with regard

to employment. The Governor had minuted: “The Mende and Temne

Headmen ought not to be called upon to act as labour contractors. They

were appointed partly for the purpose of representing to the Government

Mende or Temne grievances. If a labourer thinks he is unjustly treated

he ought to feel that his headman is his natural protector.”

Accordingly

it was made lawful under the new Ordinance for a Tribal Ruler to

"inquire into any complaint made by a labourer being a member of his

tribe, against his employer ", and if necessary to take the matter

further.

The first tribe to have a Tribal Ruler appointed under the 1905 Ordinance was the Kru. The Governor was in a hurry to get someone gazetted as soon as possible because he was at the time trying to sort out a tangle relating to the ownership of land in the Kru Reservation. He was confused by some representations made to him by a dissident section of the tribe and, rather impatiently, ordered that an election be held. Thus he departed from his own principle that Government action should be limited to recognizing an existing administration. In his Report, Mathews criticizes this practice of holding elections which afterwards became common, and that of appointing a Tribal Ruler for five years instead of for life. A similar criticism was made at the time by some Krumen who petitioned: “We do earnestly beg of Your Excellency to still retain Sgt. Jack Savage as our chief until his death, and not appointing a second one, while he is still living—which has never been done, and we are afraid will bring a never-ending confusion in Kru Town and elsewhere.” The candidate put up by the dissident section was disqualified because he had served a prison sentence for theft and the election went to a third man who proved himself an excellent Tribal Ruler.

Next came an application from the Fula for the recognition of Jamburia. Then in 1906 Governor Probyn became anxious to extend the system to the Mende. In the meantime “King George”

The first tribe to have a Tribal Ruler appointed under the 1905 Ordinance was the Kru. The Governor was in a hurry to get someone gazetted as soon as possible because he was at the time trying to sort out a tangle relating to the ownership of land in the Kru Reservation. He was confused by some representations made to him by a dissident section of the tribe and, rather impatiently, ordered that an election be held. Thus he departed from his own principle that Government action should be limited to recognizing an existing administration. In his Report, Mathews criticizes this practice of holding elections which afterwards became common, and that of appointing a Tribal Ruler for five years instead of for life. A similar criticism was made at the time by some Krumen who petitioned: “We do earnestly beg of Your Excellency to still retain Sgt. Jack Savage as our chief until his death, and not appointing a second one, while he is still living—which has never been done, and we are afraid will bring a never-ending confusion in Kru Town and elsewhere.” The candidate put up by the dissident section was disqualified because he had served a prison sentence for theft and the election went to a third man who proved himself an excellent Tribal Ruler.

Next came an application from the Fula for the recognition of Jamburia. Then in 1906 Governor Probyn became anxious to extend the system to the Mende. In the meantime “King George”

No direct evidence of what members of the City Council thought of this new system of Tribal Administration has come to light, but it is probable that they did not view it with favour. The question of Tribal Administration in the city has several times shown the existence of tension between the Creoles and the tribal population. When Alimamy Momo 2 was recognized as Tribal Ruler of the Temne in 1906 and submitted his proposed rules, it was found that these included a proposal that “the Creoles should not unnecessarily tamper with the Temne man or otherwise annoy him", which the Government promptly deleted as ultra vires. Another rule was intended to enforce the return of the marriage payment when a husband and wife separated, to which the City Council objected

1 Probyn to Crewe, 10th June, 1909.

2 A portrait of

Alimamy Momo mounted on the pony on which he used to

ride round Freetown appears in A

Transformed Colony, by T. J.

Alldridge, London, 1910, facing p. 50.

that “the operation of Native heathenish customs of marriage should be

confined to the Protectorate and be not encouraged

nor receive the

support of the laws of the Colony ". The Government upheld their

objection but the Colonial Secretary left his private opinion on

record. He minuted: “I am afraid that the Native heathenish customs of

marriage are by no means confined to the Protectorate. It might be as

well if some of these rules were enforced in so-called Christian

communities.”

In 1908 Alimamy Kangbwe was appointed Tribal Ruler of the Loko. After this date there was a gap of four years before the next tribe (Limba) applied to have their Alimamy recognized. The reader who wishes to study the extension of the system to the other tribes will find much of the relevant information in Mathews’ admirable report.

In the same year, 1908, Governor Probyn called upon the Acting Commissioner of Police for a report on how Tribal Administration in Freetown was working. The system was Probyn’s own creation and he must have felt some satisfaction when he was able to forward this very favourable report to the Secretary of State. The Acting Commissioner of Police had written that the Tribal Rulers adjudicate tribal cases, saving time and giving men an easier hearing than they would otherwise obtain. They are useful as the mouthpieces of the Government in conveying orders to the people. “They are of the greatest assistance,” he said, “in inquiring into matters for the Police when occasion demands, and in helping to bring fugitives to justice by keeping on the lookout and informing their ‘Santiggis’. The fact that there are representative men for each tribe, I am sure, is a great factor in the reduction of crime as each headman is naturally anxious to stand well with the Government. . . . The Tribal Ruler is also a local agent for members of the tribe who come down from the Protectorate and a medium for inter-tribal palavers in Freetown.”

What then caused the decline of a system which began so well? Although the Ordinance was suited to the circumstances and the personalities of its day, it was not adapted to meet the changes which followed. Formerly there were many personal acquaintanceships and ties between those who governed and those who were governed. When the Kru Tribal Ruler had a difficult problem he would go round to the Commissioner of Police in the evening and ask his advice The creation of a European Reservation (for such

it legally was) at Hill Station had a beneficial effect upon the health of officials but it broke these personal ties. When, after the 1914 war, the Tribal Administration Ordinance ceased to be used for the positive purposes for which Probyn had intended it, it was not surprising that abuses crept in. To lay the whole blame for this upon the Tribal Rulers (as has been done) is hardly fair.

In 1908 Alimamy Kangbwe was appointed Tribal Ruler of the Loko. After this date there was a gap of four years before the next tribe (Limba) applied to have their Alimamy recognized. The reader who wishes to study the extension of the system to the other tribes will find much of the relevant information in Mathews’ admirable report.

In the same year, 1908, Governor Probyn called upon the Acting Commissioner of Police for a report on how Tribal Administration in Freetown was working. The system was Probyn’s own creation and he must have felt some satisfaction when he was able to forward this very favourable report to the Secretary of State. The Acting Commissioner of Police had written that the Tribal Rulers adjudicate tribal cases, saving time and giving men an easier hearing than they would otherwise obtain. They are useful as the mouthpieces of the Government in conveying orders to the people. “They are of the greatest assistance,” he said, “in inquiring into matters for the Police when occasion demands, and in helping to bring fugitives to justice by keeping on the lookout and informing their ‘Santiggis’. The fact that there are representative men for each tribe, I am sure, is a great factor in the reduction of crime as each headman is naturally anxious to stand well with the Government. . . . The Tribal Ruler is also a local agent for members of the tribe who come down from the Protectorate and a medium for inter-tribal palavers in Freetown.”

What then caused the decline of a system which began so well? Although the Ordinance was suited to the circumstances and the personalities of its day, it was not adapted to meet the changes which followed. Formerly there were many personal acquaintanceships and ties between those who governed and those who were governed. When the Kru Tribal Ruler had a difficult problem he would go round to the Commissioner of Police in the evening and ask his advice The creation of a European Reservation (for such

it legally was) at Hill Station had a beneficial effect upon the health of officials but it broke these personal ties. When, after the 1914 war, the Tribal Administration Ordinance ceased to be used for the positive purposes for which Probyn had intended it, it was not surprising that abuses crept in. To lay the whole blame for this upon the Tribal Rulers (as has been done) is hardly fair.

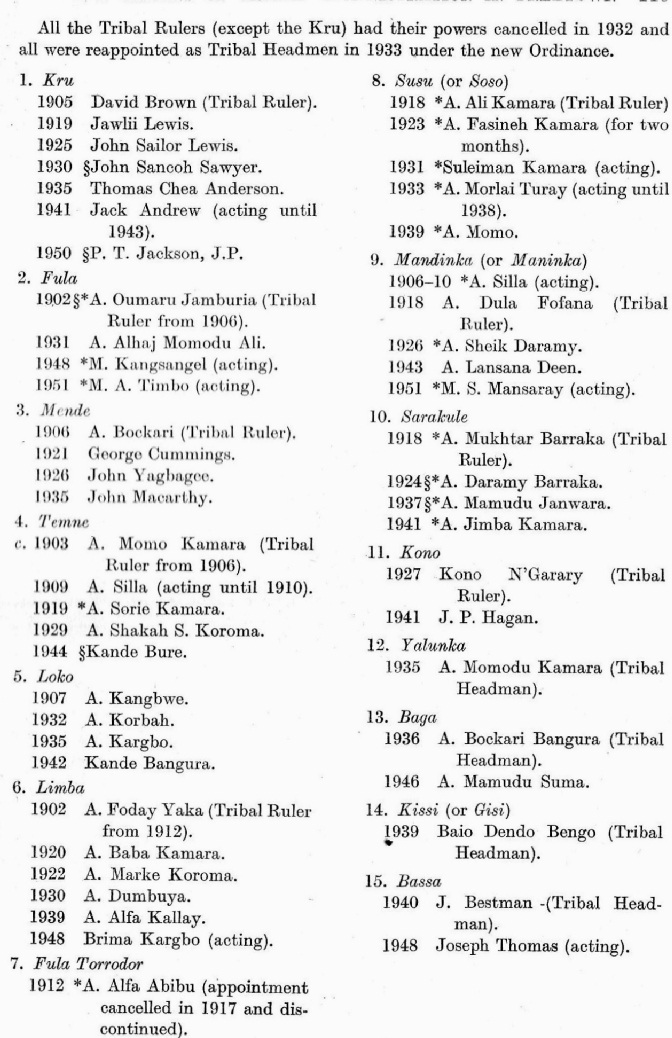

APPENDIX: CHIEFS AND ALIMAMIES

IN FREETOWN

From 1850 to the passing of the 1905 Ordinance About 1852 Mahdi

Janwara of the Sarakule was elected Alimamy over the

Maninka, Fula, and Sarakule tribes in Freetown because of the need to

have someone with authority to arrange for the reception of trading

caravans coming down from the interior. After his death about eight

years later jealousies prevented these tribes from agreeing upon a

successor and the deadlock continued for many years until the Maninka

appointed a Chief for themselves alone. The Liberated African tribes

used at first to recognize headmen and it was Atagpa Macauley, the

“King”

of the Akus, who was brought in to preside over the “coronation” of

Sorie Sillaba as Alimamy of the Maninka. Shortly afterwards the

Sarakule “crowned” Alimamy Barraka, and the Soso Alimamy Moriba.

Successive appointments among the Maninka were: Foday Silla (c. 1882),

Ali Swari (c. 1883), Amara

Silla (c. 1893), Sanussi

Daramy (c. 1897),

Cabba Salu (c. 1898). Among

the Sarakule: Sana Janwara (c.

1900),

and from 1904 Kemo Samba acted as Headman. Among the Soso: Musa Baia

Baia

(c. 1904).

It was not until the second half of the nineteenth

century that members

of the Kru tribe began to settle permanently in Freetown. Previously

they came to the Port

in bands, each with its own headman. The first resident Kru Chief may

have been Jim Boy (c. 1850)

but it is more likely to have been Prince

Albert (c. 1860). He was

succeeded by King William (c.

1870), Tom

Peter (c. 1880), and Jack

Savage (1886).

Members of the

Temne tribe in Freetown to-day remember no Headman before Alimamy

Borbor (c. 1900) but he seems

to have had one predecessor at least,

for a Freetown newspaper called The

Artisan

in its issue of 14th

October, 1885, refers to the celebration of the festival of Greater

Bairam by the Muslims and says that it was followed by "the election

by the Temne population of a headman to direct their interests in the

Colony. The Limba population on Saturday last had a grand turn out on

the

occasion of a similar election in their interests. We may hope there is

no

political significance in these novel movements ". Similarly Alimamy

Foday Yaka claimed in a letter written to the Governor in January, 1903

"since Pope Hennessy’s time [i.e.1872—3] the Limba’s King and the Temne

King have been the first kings in the Colony..." The only predecessor

to Alimamy Foday Yaka as Headman of the Limba who is remembered today

is Alimamy

Konte.

After the passing of the Ordinance in 1905

Note: A. denotes

the title of Alimamy. Kande

is a title taken by some

Paramount Chiefs; after succession they renounce their former name. §

indicates persons said to have been or to be literate in English, and *

in

Arabic. The standard of literacy has been taken as that required to

write a letter in the language—in some ways a more exacting standard in

Arabic than in English as many Muslims become proficient in reading

Arabic but have no cause to write in it.