...It was intially planned that

segregation only take place at night for

this was the time when the mosquitoes generally attacked their victims.

During the day Europeans could work on their jobs in Freetown, then

retreat to the hills in the evening to escape "the bite" which,

according to Dr. Ross was " as much to be dreaded as that of a mad

dog." 53 The area selected was to be large enough to

contain all of the European homes in the colony. It was to be

surrounded by a strip of land cleared of trees, plants, and houses,

about a quarter of a mile wide, or "of a width sufficient to defy the

powers of flight possessed by the average mosquito." Within the

segregated area itself, care was to be taken that no place existed

where mosquitoes could deposit larvae. Most important of all, the

number of African servants in the area during the day was to be reduced

to a minimum, African children were to be totally excluded, and during

the evening and night, all non-Europeans were to be kept outside the

cantonment. To prevent the encroachment of the African population,

squatting, house building, and cultivation of land within one mile of

the residential area was not to be allowed. Warning signs and fences

were to proclaim that trespassing was forbidden. 54

...It was intially planned that

segregation only take place at night for

this was the time when the mosquitoes generally attacked their victims.

During the day Europeans could work on their jobs in Freetown, then

retreat to the hills in the evening to escape "the bite" which,

according to Dr. Ross was " as much to be dreaded as that of a mad

dog." 53 The area selected was to be large enough to

contain all of the European homes in the colony. It was to be

surrounded by a strip of land cleared of trees, plants, and houses,

about a quarter of a mile wide, or "of a width sufficient to defy the

powers of flight possessed by the average mosquito." Within the

segregated area itself, care was to be taken that no place existed

where mosquitoes could deposit larvae. Most important of all, the

number of African servants in the area during the day was to be reduced

to a minimum, African children were to be totally excluded, and during

the evening and night, all non-Europeans were to be kept outside the

cantonment. To prevent the encroachment of the African population,

squatting, house building, and cultivation of land within one mile of

the residential area was not to be allowed. Warning signs and fences

were to proclaim that trespassing was forbidden. 54

The hills surrounding Freetown were ideal for the establishment of a

European enclave. The mosquito population thinned out considerably as

the land became more elevated and, except for a few cultivated patches,

the areas of planned settlements were free of existing African

habitation. A precedent for a location in the hills, moreover, had been

set years earlier when a missionary society rest house was established

on Leicester Peak.

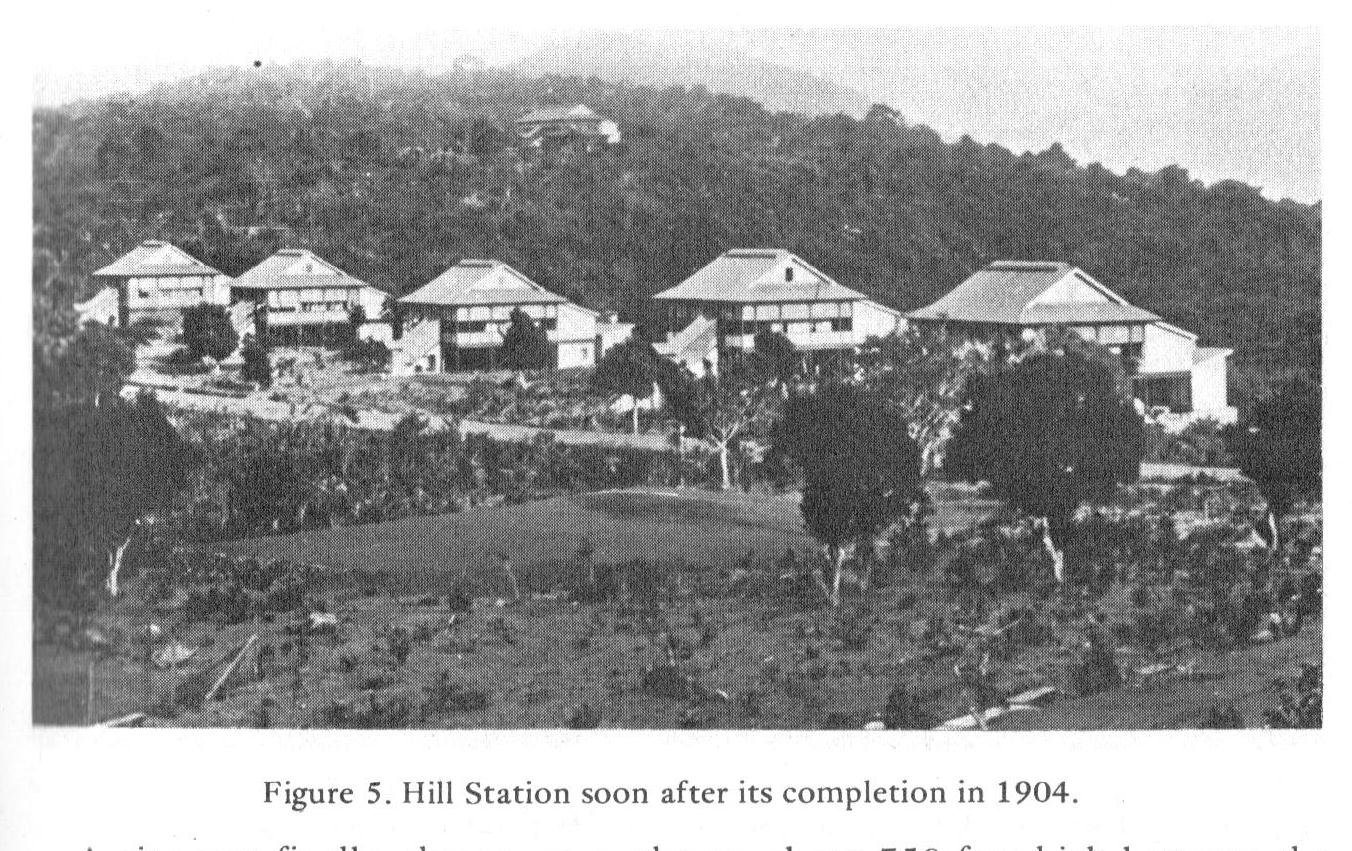

A site was finally chosen on a plateau about 750 feet high between the

villages of Regent and Wilberforce, about four miles from the center of

Freetown. Workmen began to clear the bush early in 1902 and, using

prefabricated building materials sent from England, completed twenty

bungalows and a hillside residence for the governor by 1904. For

the sake of maximum ventilation and protection from the insects and

elements, the residences uniformly faced north and were raised high

above ground on columns. The area beneath the building was covered with

cement to prevent the formation of Anopheles breeding pools. And, like

its India counterpart, the segregated settlement became known as Hill

Station.55

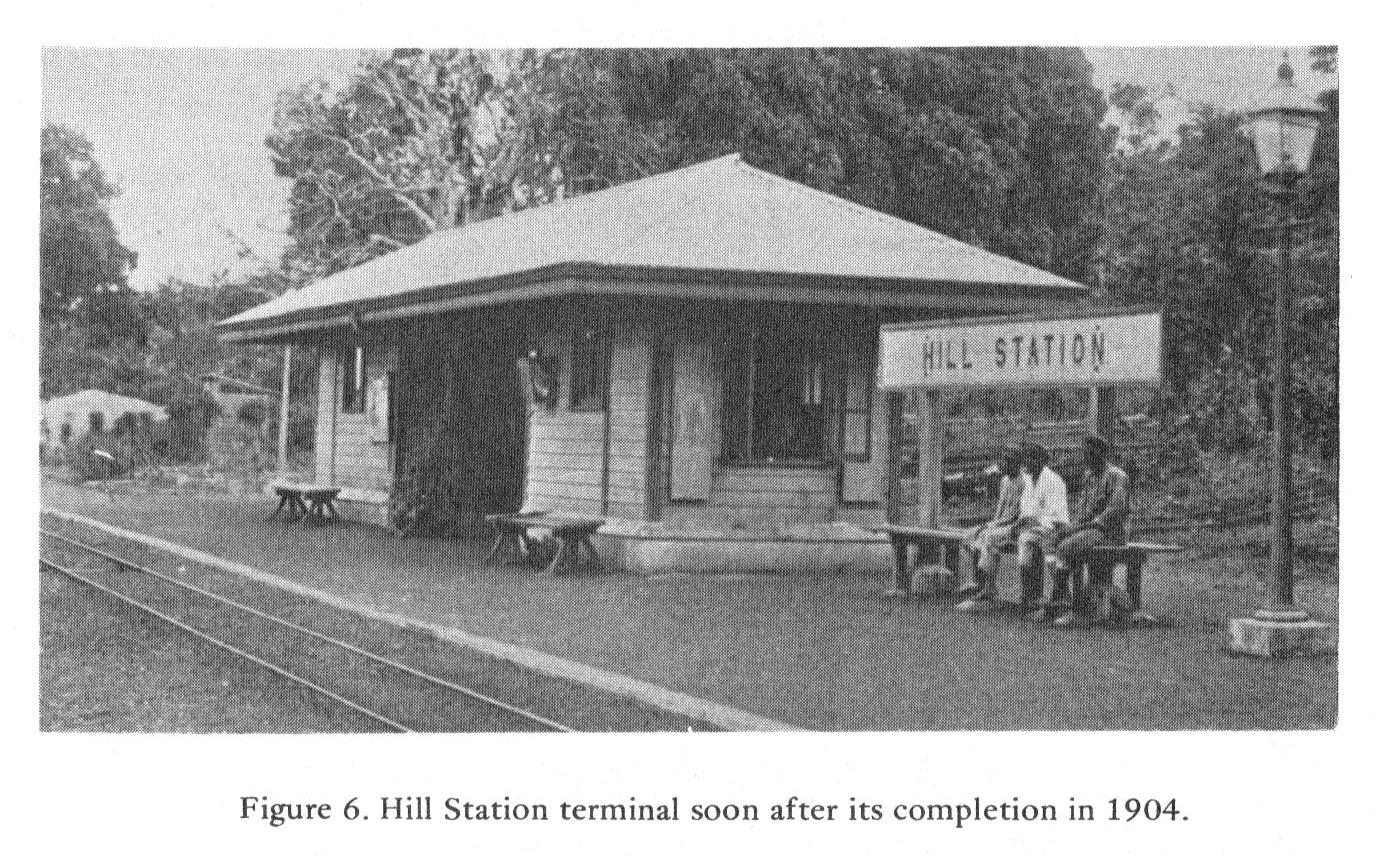

The transportation problem had yet to be considered and solved. The

only way to get to the hills at the turn of the century was by walking

on bush paths or by being carried in a hammock. Since Europeans living

in the enclave would need to commute to Freetown and back daily,

however, the success of the settlement depended on rapid, mechanized

transport. In 1902, therefore, workmen began to lay track for an

adhesion railroad between Freetown and Hill Station.56 The

"Mountain Railroad" as it came to be known, running on one of the

steepest grades ever attempted for its type of locomotive, opened for

goods and passenger traffic early in 1904. From that time until

passenger service ceased in 1929, after road-building and car transport

had made it a costly anachronism, the train made the round trip three

or four times daily with two or three carriages separated by class.57

was by walking

on bush paths or by being carried in a hammock. Since Europeans living

in the enclave would need to commute to Freetown and back daily,

however, the success of the settlement depended on rapid, mechanized

transport. In 1902, therefore, workmen began to lay track for an

adhesion railroad between Freetown and Hill Station.56 The

"Mountain Railroad" as it came to be known, running on one of the

steepest grades ever attempted for its type of locomotive, opened for

goods and passenger traffic early in 1904. From that time until

passenger service ceased in 1929, after road-building and car transport

had made it a costly anachronism, the train made the round trip three

or four times daily with two or three carriages separated by class.57

list by a single black face.66

The Mountain Railway similarly discriminated against Africans. J.A.

Fitz-John, the nimble-witted Creole editor of the Sierra Leone Times,

in his typical caustic manner, described the racial segregation which

took place at the inauguration of the track. The railway had made two

inaugural trips, one especially for Europeans - the "Segregation Party"

- in which, according to Fitz-John, "there was nothing tawney [sic] to

come between the wind and divinity of anyone of the party - not even

the Mayor," who, at this time, was C.E. Wright, a Creole; the other

trip was "exclusively for natives." "Let us trust," Fitz-John

commented,

"that the authorities fumigated the carriage afterwards, in order to

run no risks."67 Sixteen years later this color bar still

continued, its strength undiminished.

list by a single black face.66

The Mountain Railway similarly discriminated against Africans. J.A.

Fitz-John, the nimble-witted Creole editor of the Sierra Leone Times,

in his typical caustic manner, described the racial segregation which

took place at the inauguration of the track. The railway had made two

inaugural trips, one especially for Europeans - the "Segregation Party"

- in which, according to Fitz-John, "there was nothing tawney [sic] to

come between the wind and divinity of anyone of the party - not even

the Mayor," who, at this time, was C.E. Wright, a Creole; the other

trip was "exclusively for natives." "Let us trust," Fitz-John

commented,

"that the authorities fumigated the carriage afterwards, in order to

run no risks."67 Sixteen years later this color bar still

continued, its strength undiminished.

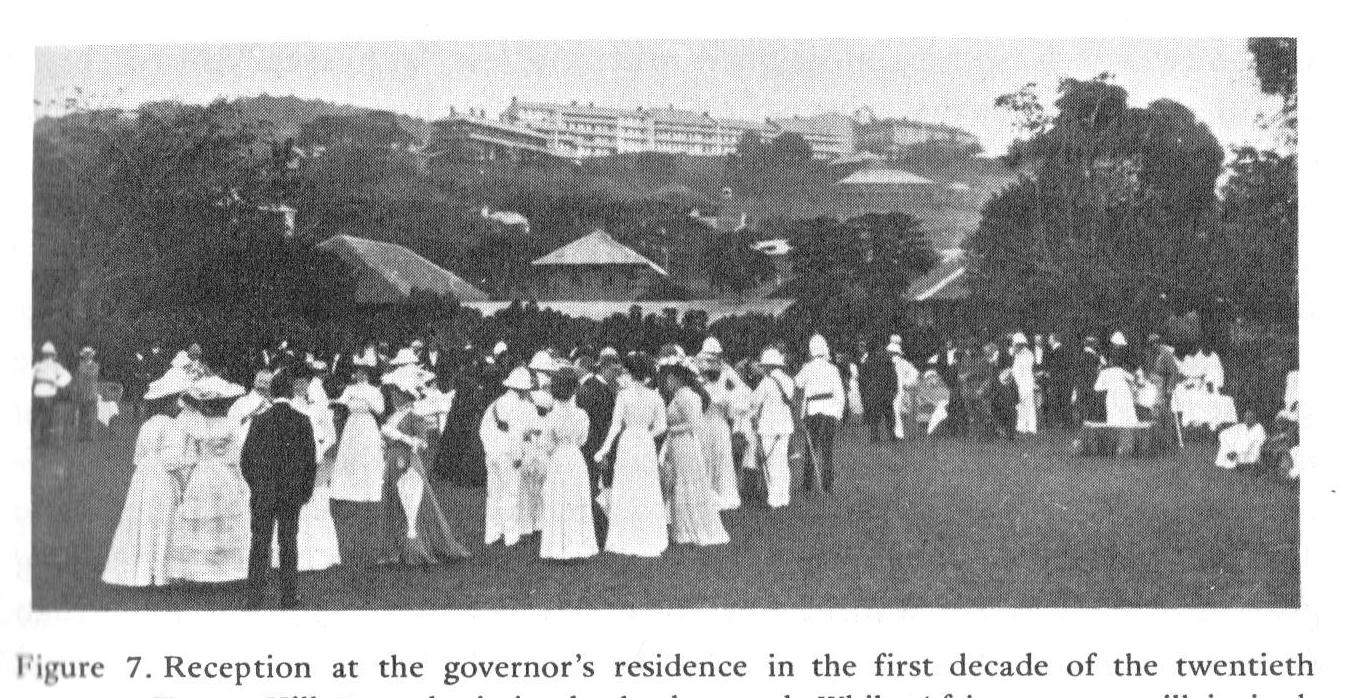

...Judging from its overall effectiveness, the Hill Station complex was

more harmful to the relationship between Creoles and Britons than it

was influential in keeping Europeans healthy. Interracial social events

in Freetown itself also became less common...The entire scheme, in

fact, was misconceived from the beginning...Its multiple failure

notwithstanding, Hill Station nevertheless continued to exist as a

limited white preserve - the most visible manifestation of Britain's

rejection of the Creoles. High above Freetown, it stood as a monument

to the deterioration of the British experiment in philanthropy and

racial equality which had led to the original founding of Sierra Leone.