From Sierra Leone Studies, No.

21, July, 1967

Kabala--The Northern Frontier Town(part 2)

By Milton Harvey,

Department of Geography, Fourah Bay College

Land Use Analysis

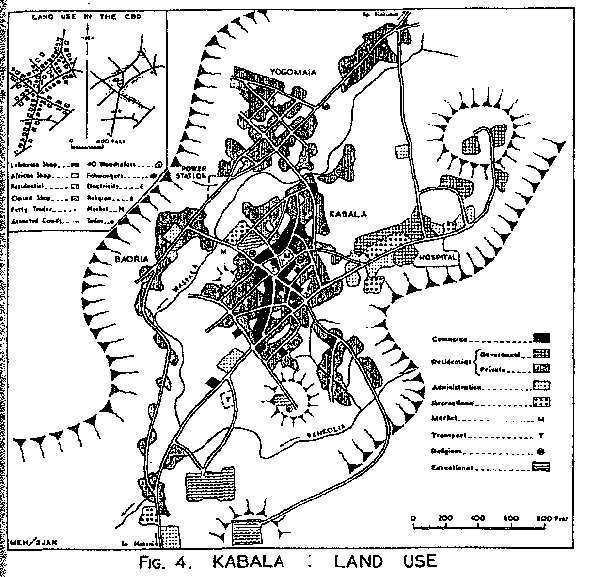

As Kabala is without any modern industries, the most important features of the urban landscape are commerce, residence, and administration. Besides these, medicine, education and recreation are also present. As in most large towns in the country, commerce in Kabala falls into three main groups: the Central Business District (CBD), the isolated all-purpose shop, and the daily market.

The star-like CBD of Kabala occupies a central location. It is bounded by such features as swamps, and break of slopes, churches and schools, an important road junction and a petrol station (Fig. 4). Right in the heart of this commercial core is the daily market which gives the CBD a hollow characteristic similar to that of Port Loko. Except for this Kabala s commercial area is compact.

As there are no European commercial firms in the town, trade is concentrated in the hands of Lebanese and Africans (Fig.

4).

Of these

two groups, the Lebanese are the main entrepreneurs and generally

occupy a central location in the CBD. The only African occupying such a

location is Lansana Kamara’s Bar close to the daily market.

Specialization in commerce is very uncommon, for as in Yonibana, most

shops sell goods ranging from provisions to fairly expensive

ready-to-wear clothes. This lack of specialization is an index of the

proemial nature of the town’s CBD. The association between shops and

tailors observed in other towns of the country is also true in Kabala.

But the CBD of Kabala unlike those of Bo, Freetown, Makeni and Kenema,

is practically devoid of petty traders, who are mainly found around the

market. Generally, where the market is within the CBD (as is also the

case in Port Loko, petty traders tend to cluster round it.

4).

Of these

two groups, the Lebanese are the main entrepreneurs and generally

occupy a central location in the CBD. The only African occupying such a

location is Lansana Kamara’s Bar close to the daily market.

Specialization in commerce is very uncommon, for as in Yonibana, most

shops sell goods ranging from provisions to fairly expensive

ready-to-wear clothes. This lack of specialization is an index of the

proemial nature of the town’s CBD. The association between shops and

tailors observed in other towns of the country is also true in Kabala.

But the CBD of Kabala unlike those of Bo, Freetown, Makeni and Kenema,

is practically devoid of petty traders, who are mainly found around the

market. Generally, where the market is within the CBD (as is also the

case in Port Loko, petty traders tend to cluster round it.The daily market of Kabala consists of two main rectangular buildings around which are small detached selling sheds. In one of these main buildings, assorted goods such as mirrors, palm oil and rice are on sale; the other is used partly as a store and partly

as a market for kola nuts. Between these two buildings, are the tables of the fish mongers—frozen, dried or smoked fish sel1ers occupying discrete positions. Because of congestion in these buildings, many traders have displayed their goods outside. Here, there is usually the tendency for people selling a particular commodity to congregate together. Thus one finds clusters of orange sellers, potato and vegetable sellers, and a large group of firewood sellers (Fig. 4).

The compact nature of the town as a whole means that the journey to either the commercial centre or the daily market is relatively easy even for people staying at Yogomaia and Baoria. Consequently, isolated all-purpose shops are very few. In fact the only examples are along Makeni Road. Thus the isolated all-purpose shop, important in less compact towns like Bo, Bonthe and Kenema, is not a viable commercial proposition in Kabala.

Kabala’s commercial land use pattern has remained stagnant for some time as no new shop has been built for over five years and may stay so for long. The Lebanese are still the most important facet in the commercial activities of the town. Paucity of large central places in this section of the country means that Kabala will remain the only important urban centre; actual comrnmercial decline is not evident. In essence, the town’s CBD is an example of an ossified shopping centre.

District administrative buildings are generally found in the east of the town where the police station, the offices of the chief clerk, the forest rangers and the post office are geographically contiguous, and separated from the offices of the District Office and the Assistant District Officer by the Police Lines. Perhaps congestion in the D.O.’s offices and the presence of Police Lines close to them, necessitated the development of a new administrative cluster. On the whole, the fringing location of district administrative offices is not a very great disadvantage since it aims primarily at serving the district, and most of the workers stay in the nearby government residences

In Kabala, there are four distinct residential groups separated by physical features such as rivers and swamps. These zones are: the Baoria residential area; the Yogomaia section; the government residential quarters; and the residential complex of Kabala. Large parts of the former two residential regions are the creation of the post-1950 period, whereas the latter two are essentially pre-1950. The Yogomaia residential section is associated mainly with Fula and Koranko;

that of Baoria with Limba. Kabala

section has a cosmopolitan

ethnic

structure including Syrian, Mandingo, Mende, Temne, Loko, Yalunka and

European.

that of Baoria with Limba. Kabala

section has a cosmopolitan

ethnic

structure including Syrian, Mandingo, Mende, Temne, Loko, Yalunka and

European.In common with other large towns in the country, the traditional circular hut is disappearing at a very fast rate (Fig. 5). In Yogomaia and Baoria, for example, it has been completely replaced by the rectangular house built of dried dirt bricks, finished with a veneer of cement and roofed with zinc. Looking at these areas from a distance, one has the impression that they are labour lines. The houses which were built around the same period are all bungalows and have similar plans. This monotony of house-types contrasts with the diversity in Kabala where modern concrete storey buildings may stand close to a one-storeyed house built either of board or zinc and covered with corrugated sheets. These contrasts reflect the gradual rate of expansion of this section. Different from the house-types in Kabala section but similar, in some ways, to those of Baoria and Yogomaia, are house-types in the government residential area of the east. The buildings of the police barracks are all similar; those of the clerks are all built on the same plan; whereas the residence of the senior civil servants are, to some extent, similar.

During the past two decades these residential regions have grown at different rates and methods. Yogomaia and Baoria have grown fastest—mainly by ribbon development. In the Kabala area the comparatively slow growth has been mainly in the form of interstitial infilling. The government residential area has hardly changed.

Although the shape of the different residential areas reflect clearly the orientation of the mountain ranges around the town the direction of flow of the main streams, and the distribution of swamps, superstition also seems to have had some influence. The buffer area between Yogomaia and Kabala has remained unused because of the belief that it is the home of a river devil—in the form of a snake. People even today never like crossing this swamp at night.

The residential unit in Kabala is usually a rectangular bungalow. For the Fula community, however, it is a compound consisting of a bungalow and one or more small gable-roofed buildings. These latter houses are found inside the compound and have no direct contact with the street, hence their occupants have to pass through the main bungalow to reach it.

Kabala also has other types of land use. Of these, medicine, education and religion are the most important. This town has the only hospital in the whole of Koinadugu District. Other medical establishments in the district consist of a mission dispensary at Yiffin; a health centre at Falaba; and treatment centres at Fadugu, Bendugu, Koinadugu and Bafodea. Kabala is therefore the most important medical centre in the district. Consequently, the raison d’Ítre for hospital location in the town should not be geographical centrality, but the availability of land for expansion. Within the town itself the peripheral location of the hospital is not a disadvantage, Kabala being a compact settlement.

The educational facilities in the town are also concentrated in the Kabala sector, the section with the largest population. There are two main primary schools, the Roman Catholic school and the District Council school; a newly founded (1961) secondary school; and a school mainly for the children of American missionaries on a hill just outside the precincts of the town. All these educational institutions are spatially distinct and have been so located that there is room for future expansion. The District Council school is found just north-west of the CBD; the Catholic primary one is situated on a small hill on the quieter south-western periphery; and the secondary school is found just off the main Makeni road near the Catholic primary school.

The secondary school’s peripheral location is no disadvantage for it is the only one in the town and it is designed to serve the whole district. Since it is a boarding school, it also caters for pupils from places like Freetown, Bonthe, Sefadu and Kailahun. Here, the desire to study outside one’s immediate vicinity is evident.

The population of the town includes both Christians and Muslims, although the Muslims far out-number the Christians. Kabala has two churches and two mosques. The Catholic Church is situated very close to the Catholic Primary school; and the Anglican Church, which is infrequently used, is within the District Council school compound, that is located in a central place which might be easily reached from all sections of the town.

Of the two mosques, the ‘Town Mosque’ is situated close to the market in the Kabala section, while the other, the ‘Fula Mosque’ is found in Yogomaia. The location of these two mosques is rational. Since the ‘Town Mosque’ is supposed to serve the whole town, a relatively central location is very advantageous. The ‘Fula Mosque’, built in the early 1950’s under the direction of Pa Alimamy Jalloh, is naturally situated in Yogomaia where the bulk of the population is Fula. Looking at it from another angle, it may be seen that the Town Mosque is found in the Wara Wara YagaIa chiefdom, whilst the Fula Mosque is in the Sengbe chiefdom. The idea of being different seems to be stronger among the inhabitants (the Fula) of Yogomaia than among those of either Baoria (with its predominance of Limba) or Kabala. This idea may also have been perpetuated by the fact that Baoria and Kabala sections are in the same chiefdom, whereas Yogomaia, because of historico-political reasons is in the Sengbe chiefdom. The distribution of slaughter houses also reflects this distinction between the two chiefdoms, for one is located in Yogomaia whereas the other is between Baoria and Kabala. Here we see examples of political factors influencing urban land use patterns.

Besides the infrequent dances at the Community Centre or at the Flamingo night club situated on the Barracks Road, football is the only popular means of recreation in Kabala. In addition to a public playing field at Yogomaia, all the schools and the police have playing fields. Matches are often played between local teams, but sometimes select teams from the other districts come to play. These games are usually followed by dances at the Community Centre. The public playing field at Yogomaia was previously the place where the inter-town or inter-chiefdom wrestling matches were held. The wrestling competitions have been discontinued and Kabala is now mainly dependent on football. A lawn tennis court found close to the Prisons is used by only a few people, and does not attract spectators. The Flamingo night club along Barracks Road, is mainly patronized by visitors and children, for women are prevented either by their husbands or on religious grounds from attending night clubs. The recreational facilities in the town are poor and should be considerably improved.

Demographic and Occupational Analysis

Although Kabala’s rates of growth are less than those of Makeni, Magburaka and Lunsar, the town’s population is still increasing. This centre’s population increased from 1,005 (for Kabala and the Barracks) in 1929 to 3,064 in 1946. By 1952, the population was 3,182 and at the time of the 1963 census, there were about 4,610 people in the town.

This marked increase in the 1929/46 period arises from the fact that in 1929, Kabala and the Barracks constituted a single settlement distinct from both Baoria and Yogomaia, but in 1946 the four were regarded as one. The small increase during the l947/52 growth phase was due to the fact that in-migration from the rural areas had slackened, as more southerly centres became great attractions for employment and social services. In Kabala, at the same time there were practically no new activities to attract a large number of people. The population increase in the 1953/63 period is probably due to the fact that the 1952 figure was an estimate (hence large margins of error), whereas the 1963 one was based on an actual census. Furthermore, this increase reflects the large influx of Fula from Guinea to northern Sierra Leone.

Kabala, like many other centres outside the mining areas, has an excess of females. Actually, there are 1,028 females to every 1,000 males. This female predominance may be due to the fact that most of the young men prefer to migrate to more prosperous parts of the country, especially the Freetown peninsula and the mining areas. The widespread nature of polygamy in Kabala may also help explain this female excess. In the predominantly polygamous Fula section of Yogomaia, for example, there were 1,139 females to 1,000 males.

Kabala has an active population

(i.e. between 15-64 years) of 2,530

i.e. 54.9% of the total population. Of the remaining population, 42.8%

are in the young age group of 0-14 years; only 2.3% are in the “older

years” group.

Kabala has an active population

(i.e. between 15-64 years) of 2,530

i.e. 54.9% of the total population. Of the remaining population, 42.8%

are in the young age group of 0-14 years; only 2.3% are in the “older

years” group.Some special features about the age structure of Kabala (Table 1) considered as a whole are: the excess of males in the 65 + age group; the excess of females in the 0-5 years group, and the excess of males in the 5-14 years sector. In the active age group (15-64) females out-number males.

The population composition of Kabala is very diverse, but besides the Koranko-Yalunka-Limba group, the Fula and the Mandingo are the largest groups. Although different tribes do not occupy specific sections of the town, it is evident that Fula are the most numerous in Yogomaia, whereas the Limba are predominant in Baoria. In Kabala, the Koranko-Yalunka group and the Fula are the most important.

The general relationship among the different tribal groups is cordial although the Fula seem to prefer the Mandingo to the Limba; this is clearly reflected by the fact that the population of Yogomaia section is almost practically composed of only Fula and Mandingo.

The Fula are mostly cattle owners; the Mandingo, petty traders; the Limba, farmers; whilst the Koranko-Yalunka group are

engaged in diverse jobs ranging from teaching through administration to farming.

According to the 1963 census, 1,454 people above the age of 10 years were employed in Kabala. In other words, 31.7% of the total population were employed, or 48.7% of the population over 10 years of age had some gainful employment. Occupational breakdowns of this employed population (Table 2) show that 33.5% work in agriculture, and forestry. Of the twelve district headquarters, this percentage is only lower than those for Kailahun (41.0), and Sefadu (37.9). Within the actual secondary and tertiary sector, commerce is the most important group employing about 22.1%. This reflects the town’s importance as a local collecting and distributing centre. But all the other district centres of the northern province have higher percentages employed in this group - Magburaka (31.2), Makeni (30.2), Kambia (24.0), Port Loko (25.2).

Kabala’s importance as an

administrative, educational and medical

centre is clearly evident from the fact that 14.3% of the gainfully

employed population work in services. This percentage is, however, low

in comparison to 21.9% for Freetown, 19.4% for Bonthe and 24.5% for

Kissy. Actually in Kabala itself, more people are engaged in

manufacturing (16.4%) than in services. This 16.4% in manufacturing are

engaged in the making of native dyed cloths (gara, and wax work), the

slaughtering of cattle, the tanning of hides, and the manufacturing of

miscellaneous handicrafts and food products. Of the other occupational

groups, transport, storage and communications is the most important

(7.2%). Here the nodal status of Kabala is evident.

Kabala’s importance as an

administrative, educational and medical

centre is clearly evident from the fact that 14.3% of the gainfully

employed population work in services. This percentage is, however, low

in comparison to 21.9% for Freetown, 19.4% for Bonthe and 24.5% for

Kissy. Actually in Kabala itself, more people are engaged in

manufacturing (16.4%) than in services. This 16.4% in manufacturing are

engaged in the making of native dyed cloths (gara, and wax work), the

slaughtering of cattle, the tanning of hides, and the manufacturing of

miscellaneous handicrafts and food products. Of the other occupational

groups, transport, storage and communications is the most important

(7.2%). Here the nodal status of Kabala is evident.Urban Problems

Kabala is not within easy reach of any large or reliable source of water. This fact coupled with the growing population of the town has made healthy drinking water a scarce commodity. Plans to dig artesian wells have temporarily failed since the parent rock underneath the whole town consists of very thick, impenetrable igneous and metamorphic rocks. In the Five-Year Development Plan, the question of supplying Kabala with water is a top priority.

The town’s actual site may have some advantages such as its being a gap, but its geographical location in Sierra Leone makes it outlandish and isolated; Makeni, the nearest. large urban centre, is 76 miles away. The difficulty of getting commodities to and from Freetown is quite considerable. It is not therefore surprising that half a pint of Guinness is forty cents (four shillings), whereas in Freetown it is thirty cents (three shillings). Actually, the area around Kabala is suitable for the economic production of vegetables, but the problems of easy accessibility to market tends to discourage increased output. A suggestion that vegetables may be sent out by air does not seem at present to be a sound economic proposition. Perhaps new methods of production and marketing may ease the situation. Previously, farmers were able to learn about new techniques and new plant types from Agricultural Shows, but none has been organized in the town since 1953.

Kabala’s “out-of-the-way” location has also had a great influence on education in the town. Since teachers all over the country get a flat rate of three pounds for travelling, those outside the Koinadugu District never like going to work in Kabala. This is understandable since it costs far more than the travelling allowance to make a return journey from (say) Freetown, Bo, Bonthe, or Kailahun to Kabala. Thus the recruitment of staff is a great problem which may only be solved if the policy of paying travelling allowance is changed, or if teachers are given other inducements.

The town’s hospital is ill-equipped: most of the modern amenities such as X-ray equipment are absent. Consequently, serious cases are usually sent by road to Magburaka—a distance of about 90 miles. Because of the distance and the arduousness of the journey, patients sometimes die on the way.

The problems of Kabala are many, and they can only be solved by serious planning of the central government. In the Five Year Development Programme there are plans to help solve the above discussed problems. But the people of Kabala can also help in this by the development of a sense of co-operation, such as the formation of co-operatives, e.g. a vegetable co-operative and a (now defunct) cattle co-operative.

Kabala has many functions which it performs for the whole district, but in some cases—as in education and medicine—these functions are quite inadequate. Consequently, it is itself dependent on towns like Magburaka and Makeni.

Kabala is nevertheless an important commercial and administrative frontier town, whose potential has unfortunately not been appreciated either during the colonial period or since independence.